-

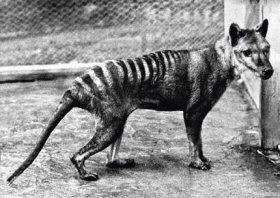

In loving memory of thylacine

The thylacine is my favorite animal.They are extinct.But some people think that there are some left in Tasmania.I do.

The modern Thylacine first appeared about 4 million years ago. Species of the Thylacinidae family date back to the beginning of the Miocene; since the early 1990s, at least seven fossil species have been uncovered at Riversleigh, part of Lawn Hill National Park in northwest Queensland.Dickson's Thylacine (Nimbacinus dicksoni), is the oldest of the seven discovered fossil species, dating back to 23 million years ago. much smaller than its more recent relatives.This thylacinid was much smaller than its more The largest species, the Powerful Thylacine (Thylacinus potens) which grew to the size of a wolf, was the only species to survive into the late Miocene. In late Pleistocene and early Holocene times, the modern Thylacine was widespread (although never numerous) throughout Australia and New Guinea.

The skulls of the Thylacine (left) and the Timber Wolf, Canis lupus, are almost identical although the species are unrelated. Studies show the skull shape of the Red Fox, Vulpes vulpes, is even closer to that of the Thylacine.

An example of convergent evolution, the Thylacine showed many similarities to the members of the Canidae (dog) family of the Northern Hemisphere: sharp teeth, powerful jaws, raised heels and the same general body form. Since the Thylacine filled the same ecological niche in Australia as the dog family did elsewhere, it developed many of the same features. Despite this, it is unrelated to any of the Northern Hemisphere predators.The indigenous peoples of Australia made first contact with the Thylacine. Numerous examples of Thylacine engravings and rock art have been found dating back to at least 1000 BC.[11] Petroglyph images of the Thylacine can be found at the Dampier Rock Art Precinct on the Burrup Peninsula in Western Australia. By the time the first explorers arrived, the animal was already rare in Tasmania. Europeans may have encountered it as far back as 1642 when Abel Tasman first arrived in Tasmania. His shore party reported seeing the footprints of "wild beasts having claws like a Tyger". Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne, arriving with the Mascarin in 1772, reported seeing a "tiger cat".The indigenous peoples of Australia made first contact with the Thylacine. Numerous examples of Thylacine engravings and rock art have been found dating back to at least 1000 BC.[11] Petroglyph images of the Thylacine can be found at the Dampier Rock Art Precinct on the Burrup Peninsula in Western Australia. By the time the first explorers arrived, the animal was already rare in Tasmania. Europeans may have encountered it as far back as 1642 when Abel Tasman first arrived in Tasmania. His shore party reported seeing the footprints of "wild beasts having claws like a Tyger"he Thylacine resembled a large, short-haired dog with a stiff tail which smoothly extended from the body in a way similar to that of a kangaroo. Many European settlers drew direct comparisons with the Hyena, because of its unusual stance and general demeanour.[10] Its yellow-brown coat featured 13 to 21 distinctive dark stripes across its back, rump and the base of its tail, which earned the animal the nickname, "Tiger". The stripes were more marked in younger specimens, fading as the animal got older.[19] One of the stripes extended down the outside of the rear thigh. Its body hair was dense and soft, up to 15 mm (0.6 in) in length; in juveniles the tip of the tail had a crest. Its rounded, erect ears were about 8 cm (3.1 in) long and covered with short fur.[20] Colouration varied from light fawn to a dark brown; the belly was cream-coloured.[21]

The mature Thylacine ranged from 100 to 130 cm (39 to 51 in) long, plus a tail of around 50 to 65 cm (20 to 26 in).[22] The largest measured specimen was 290 cm (9.5 ft) from nose to tail.[21] Adults stood about 60 cm (24 in) at the shoulder and weighed 20 to 30 kg (40 to 70 lb).[22] There was slight sexual dimorphism with the males being larger than females on average.[23]

The female Thylacine had a pouch with four teats, but unlike many other marsupials, the pouch opened to the rear of its body. Males had a scrotal pouch, unique amongst the Australian marsupials,[24] into which they could withdraw their scrotal sac.[19]

The Thylacine was able to open its jaws to an unusual extent: up to 120 degrees.[25] This capability can be seen in part in David Fleay's short black-and-white film sequence of a captive Thylacine from 1933. The jaws were muscular and powerful and had 46 teeth.[20]

The Thylacine's footprint is easy to distinguish from those of native and introduced species.

Thylacine footprints could be distinguished from other native or introduced animals; unlike foxes, cats, dogs, wombats or Tasmanian Devils, Thylacines had a very large rear pad and four obvious front pads, arranged in almost a straight line.[26] The hindfeet were similar to the forefeet but had four digits rather than five. Their claws were non-retractable.[19]

The early scientific studies suggested it possessed an acute sense of smell which enabled it to track prey,[26] but analysis of its brain structure revealed that its olfactory bulbs were not well developed. It is likely to have relied on sight and sound when hunting instead.[19] Some observers described it having a strong and distinctive smell, others described a faint, clean, animal odour, and some no odour at all. It is possible that the Thylacine, like its relative, the Tasmanian Devil, gave off an odour when agitated.[27]

The Thylacine was noted as having a stiff and somewhat awkward gait, making it unable to run at high speed. It could also perform a bipedal hop, in a fashion similar to a kangaroo—demonstrated at various times by captive specimens.[19] Guiler speculates that this was used as an accelerated form of motion when the animal became alarmed. The animal was also able to balance on its hind legs and stand upright for brief periods.[28]

Although there are no recordings of Thylacine vocalisations, observers of the animal in the wild and in captivity noted that it would growl and hiss when agitated, often accompanied by a threat-yawn. During hunting it would emit a series of rapidly repeated guttural cough-like barks (described as "yip-yap", "cay-yip" or "hop-hop-hop" wink , probably for communication between the family pack members.[29] It also had a long whining cry, probably for identification at distance, and a low snuffling noise used for communication between family members.[30]The last captive Thylacine, later referred to as "Benjamin" (although its sex has never been confirmed) was captured in 1933 and sent to the Hobart Zoo where it lived for three years. Frank Darby, who claimed to have been a keeper at Hobart Zoo, suggested "Benjamin" as having been the animal's pet name in a newspaper article of May 1968. However, no documentation exists to suggest that it ever had a pet name, and Alison Reid (de facto curator at the zoo) and Michael Sharland (publicist for the zoo) denied that Frank Darby had ever worked at the zoo or that the name Benjamin was ever used for the animal. Darby also appears to be the source for the claim that the last Thylacine was a male; photographic evidence suggests it was female.[55][56] This Thylacine died on 7 September 1936. It is believed to have died as the result of neglect—locked out of its sheltered sleeping quarters, it was exposed to a rare occurrence of extreme Tasmanian weather: extreme heat during the day and freezing temperatures at night.[57] This Thylacine features in the last known motion picture footage of a living specimen: 62 seconds of black-and-white footage showing it pacing backwards and forwards in its enclosure in a clip taken in 1933 by naturalist David Fleay.[58][59] National Threatened Species Day has been held annually since 1996 on 7 September in Australia, to commemorate the death of the last officially recorded Thylacine.[60]

"Benjamin" yawning in 1933

Although there had been a conservation movement pressing for the Thylacine's protection since 1901, driven in part by the increasing difficulty in obtaining specimens for overseas collections, political difficulties prevented any form of protection coming into force until 1936. Official protection of the species by the Tasmanian government was introduced on 10 July 1936, 59 days before the last known specimen died in captivity.[61]

The results of subsequent searches indicated a strong possibility of the survival of the species in Tasmania into the 1960s. Searches by Dr. Eric Guiler and David Fleay in the northwest of Tasmania found footprints and scats that may have belonged to the animal, heard vocalisations matching the description of those of the Thylacine, and collected anecdotal evidence from people reported to have sighted the animal. Despite the searches, no conclusive evidence was found to point to its continued existence in the wild.[10]

The Thylacine held the status of endangered species until 1986. International standards state that any animal for which no specimens have been recorded for 50 years is to be declared extinct. Since no definitive proof of the Thylacine's existence had been found since "Benjamin" died in 1936, it met that official criterion and was declared officially extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.[2] The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is more cautious, listing it as "possibly extinct".[6

Miss you thylacine.

- by Twihard-Twifan |

- Non Fiction

- | Submitted on 04/20/2009 |

- Skip

- Title: Tasmanian Tiger/thylacine

- Artist: Twihard-Twifan

- Description: Oh

- Date: 04/20/2009

- Tags: tasmanian tigerthylacine

- Report Post

- Reference Image:

-

Comments (0 Comments)

No comments available ...